The case

The case

Ten years before videos of a police officer suffocating George Floyd launched nationwide protests, Jamail Amron called 911 asking for help. Paramedics arrived, followed by deputies with Harris County Constable Precinct 4.

From there, the details diverge, depending on who is telling the story. Regardless, it ends with Amron being pronounced dead at the hospital a short time later. Understandably, Amron’s parents struggled to see how the events, as described by law enforcement, could have led to their son’s death. Their search for clarity connected them with South Texas College of Law Houston alumnus Brad Gilde ’04.

An accomplished trial attorney, Gilde would spend nearly a decade pursuing justice for Amron’s family. Along the way two additional STCL Houston alumni, Andrew Bender ’12 and Sharon McCally ’90, would join the fight. Though their time at the law school spanned nearly 25 years, the passion and talent cultivated in the advocacy program was both an important bond and a tactical advantage.

The trial

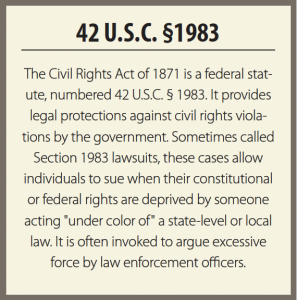

Despite the challenges that come with pursuing a 42 U.S.C. §1983 civil rights complaint, Gilde signed on as lead attorneyin fall 2012, just before the statute of limitations expired.

Despite the challenges that come with pursuing a 42 U.S.C. §1983 civil rights complaint, Gilde signed on as lead attorneyin fall 2012, just before the statute of limitations expired.

Gilde had extensive litigation experience. He knew these types of cases were unique and the options for finding representation were limited. Amron’s parents, Ali Amron and Barbara Coats, had previously approached several other attorneys, and they all declined to take the case.

“I find constitutional law, and specifically civil rights cases, to be the most complicated and difficult from a legal and a trial standpoint,” Gilde said. “We’ve got some of the best lawyers in the world in this city, but I can count on one hand the number of lawyers I would feel comfortable sending a civil rights or constitutional case.”

While the similarities of what happened to Jamail Amron and George Floyd are apparent, a significant difference created one of Gilde’s biggest hurdles.

“Amron’s death happened in September 2010, before cell phone cameras were omnipresent, so we had to rely on the eyewitness testimony of one person,” Gilde said. “The cameras and mics that were in place should have been on and recording at the time of the incident, according to police policies. But they were not.”

Not surprisingly, the political, social and tactical realities of trying these cases only add to their unpopularity among attorneys.

“When I began litigating the case in 2012, everything was met with hostility from Harris County,” Gilde said. “Everything was met with motions to compel. When we got information, it was boxes and boxes and boxes we had to sort through. Also, if you’re suing a city or a county where you live, where you pay taxes, you’re perhaps inflicting pain on yourself. And if you end up on appeal, you have to roll the dice on whose courtroom you’re going to land in and how that impacts your likelihood of success.”

The team

Knowing the odds were not necessarily in his favor, Gilde enlisted the help of a fellow STCL Houston graduate he knew to be an outstanding brief writer and appellate attorney. Bender came on board in 2015 to assist with an interlocutory appeal during the pre-trial phase.

“This case really checked all the boxes for me,” Bender said. “Even at that time, we were in the wake of the unrest in Ferguson, and there was already a national movement underway regarding police brutality and people of color. I knew this was an important opportunity to help a family seeking justice, and also to develop better law.”

Bender would remain part of the team as the trial began in 2017. At the conclusion of the arguments, a jury deliberated six hours before unanimously awarding just over $11 million to Amron’s parents. The win was a long time coming.